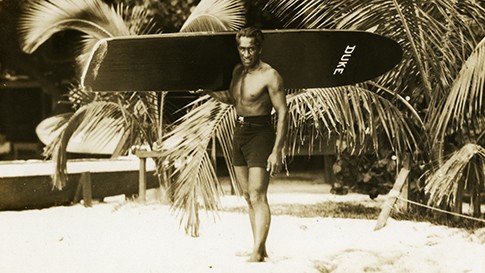

Duke Kahamamoku, champion Hawaiian surfer and swimmer, who popularised the burgeoning sport of surfing in Australia at Freshwater Beach during the summer of 1914/15, is one of 21 people NSW Heritage is recognising with distinctive blue plaques. They will appear on buildings associated with the high achievers, to celebrate their creative endeavours.

On 18 April 2022 NSW Heritage Minister James Griffin MP announced that 17 influential people from the world of sport, science, politics, religion, arts and social welfare were selected to be among the first blue plaques, with more to follow.

They were chosen from over 750 nominations from the public, community organisations and local councils.

The new 17 were in addition to an initial four plaques that were disclosed when the project was first announced in June 2021. Among them are May Gibbs, children’s author-illustrator; Caroline Chisholm, advocate for women and refugees; Charles Perkins, Aboriginal activist; Nancy Bird Walton, aviator; and Brett Whiteley, artist.

The plaques are derived from a similar scheme in Britain founded by English Heritage over a century ago, which mark the homes and workplaces of life-changing Britons throughout history, including authors, scientists, actors and campaigners.

NSW Heritage revealed: “The Blue Plaques program aims to capture public interest and fascination in people, events and places that are important to the stories of NSW. It is inspired by the famous London Blue Plaques program run by English Heritage which originally started in 1866, and similar programs around the world.”

Duke Kahamamoku’s plaque will likely be affixed in the vicinity of the Freshwater Surf Life Saving Club (SLSC) at the beach he is most closely associated with in Australia.

Freshwater SLSC resident historian Eric Middledorp has liaised with NSW Heritage on the siting and wording of the blue plaque.

Eric revealed to Manly Observer that when he joined Freshwater Surf Cub in 1964 he met older surfers who recalled meeting Duke and watching his demonstrations in the summer of 1914-15.

Just north of Freshwater Beach on the Freshwater headland, a bronze statue of Duke stands atop a board surfing the crest of a sandstone rock in the aptly-named Duke Kahanamoku Park.

The life-size figure overlooks 24 circular mosaics of distinguished Australian surfers – 16 men and 8 women – including Wayne Bartholomew, Wendy Botha, Pam Burridge, Midget Farrelly and Nat Young.

Friends of Freshwater community group is currently campaigning to have the mosaics refurbished and the park renovated, because they’ve deteriorated through a combination of weathering and neglect since their installation in 1994.

Duke Kahanamoku, inspiration

Duke Kahanamoku arrived in Australia after a two-week ocean voyage on 14 December 1914. Duke was not in Australia to solely promote surfing but to compete in many swimming events, having recently won a gold medal in the 100metres freestyle at the Olympic Games in Stockholm (May-July 1912).

Despite the surfing accolades that followed him, Duke actually arrived in Sydney after a two-week sea voyage without a surfboard – believing they were banned in Australia. He commissioned George Hudson’s carpenters in Glebe to design and roughly prepare the board for Duke to finish off and shape from sugar pine (because Duke’s preferred redwood was unavailable). At eight foot six inches (262cm) in length – Duke stood six foot one inches tall (186cm) – which the Sydney Sun newspaper described as “almost that of a coffin lid,” and weighing a hefty 40kg (modern ‘Malibu’ boards weigh around 15kg), it is now on display inside a clear case in Freshwater Surf Life Saving Club.

“Duke’s original board is probably the most important piece of surfing memorabilia in Australia,” declared Eric, who helped make and later surfed upon an exact replica of Duke’s board, also on display at Freshwater SLSC.

Duke, who reportedly learnt water confidence as a boy after an uncle paddled him out into the ocean in an outrigger canoe and threw him off the side, was discovered in 1911, aged 21, after winning a 100 yards freestyle race between two piers in Honolulu Harbour.

What astonished observers was his time – 55.4 seconds – which knocked 4.6 seconds off the 60 seconds official record. Duke also tied the world record of 24.2 seconds in the 50-yard freestyle.

A year later at the USA swimming trials he broke the 200 metre freestyle world record, which led to his inclusion in the USA swimming squad at the Stockholm Olympics, where he set another record.

Duke is credited with popularising surfing in Australia when he gave surfing demonstrations at Freshwater on Christmas Eve of 1914 and, most notably, 10 January 1915 where he entertained a large crowd, showing off his board techniques and tricks.

His brother later recalled that lifeguards on duty warned Duke of sharks in the vicinity. When asked after his performance whether he’d seen any, Duke replied, “Yes, I saw plenty.” He was then asked, did they bother him? To which he replied, “No, and I didn’t bother them!”

Duke put on further displays of his surfing skills including tandem surfing (with young Northern Beaches local, Isabel Letham), at Dee Why Beach and Cronulla Beach on 6 and 7 February, plus an unscheduled appearance at Bondi Beach, before relocating to New Zealand for public demonstrations on 7 and 13 March 1915, which also had the effect of popularising the sport there.

The rest is history, with Duke going on to wow the big crowds gathered at his exhibitions, to watch him effortlessly catching waves. These widely publicised Exhibitions lit the fuse to popularise surfing in Australia.

Years later, in the foreword he wrote for The Surfrider, Duke recalled, “There was a tiny little girl in the crowd that day who by her manner seemed more excited than all in the crowd. I put her up on my shoulders and we made a few good rides.”

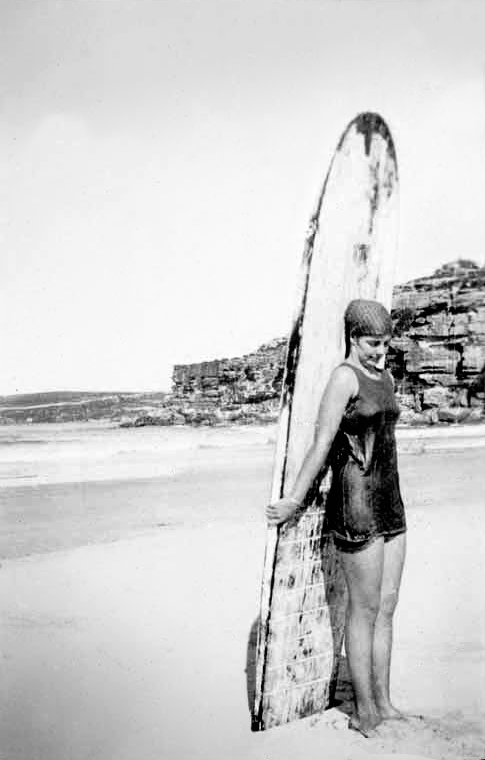

Isabel Letham herself recalled their cooperative ride to Women’s Weekly in 1954, performed at a time when female surfing and mixed race socialising was generally taboo in Australia, although women surfed in Hawaii. “I was really frightened but the Duke took me by the scruff of the neck, stood me before him, and we took the shoot.”

Letham went on to become one of Australia’s first female surfers, despite her father’s disapproval, wearing a two-piece bathing suit that also defied social conventions. She revealed to Women’s Weekly, “My father thought the sport dangerous, and wasn’t at all pleased at my taking it up. If he saw me out with the board, he was usually rather annoyed. There would have been a deadlock over this but for the fact that I arranged for a lookout at the Freshwater Life Saving Clubhouse to ring the shark bell when father came in sight over the hill.”

Tommy Walker and Aboriginal surfing

It is important to remember that Duke was not the first surfer to ride waves in Australia. Despite being credited with ‘introducing’ surfing to Australia, the sport was here already, albeit in its infancy, although Duke, in his own words, “showed the Australians how it was done.”

Although ‘surfbathing’ was popular, there were only a relatively small number of surfboard riders, such as Tommy Walker and others from Manly and other Australian beaches, undertaking surfboard ‘riding’ in the early 1900’s.

“The surf club movement started in around 1906,” Eric Middledorp told Manly Observer. Only a few years earlier it was illegal to swim in the sea and people usually swam at night to avoid the ban.”

Between 1838 and 1902, day swimming in the sea was prohibited in metropolitan municipalities, including Manly, under the Sydney Police Act. Manly Council introduced a by-law in 1878 forbidding bathing in the surf between 7am and 8pm.

Although swimming at Freshwater Beach was permitted, violators who swam at Manly faced arrest by the Council’s Inspector of Nuisances.

This Law was challenged in 1902 by aspiring politician and owner-publisher of the Manly and North Sydney News, William Gocher, who deliberately flouted the rules in October 1902, challenging the authorities to arrest him. He was ignored, but the following year Manly Council voted to repeal the ban.

Manly local, Tommy Walker, is arguably responsible for introducing modern surfing to Australia, when he returned from a 1908-9 trip to Waikiki, Hawaii, as a crew member aboard HMS Poltalloch, with a 10 foot (300cm) board he purchased there for two dollars.

As Tommy’s board riding skills developed, he gave demonstrations of his prowess in both Manly and Yamba, where his ship routinely docked. He also undertook a surfing demonstration at the second Freshwater Life Saving Carnival on 26 January 1912 – almost a year before Duke gave his famous performances at the same beach – which the Telegraph reported the following day: “A clever exhibition of surf board shooting was given by Mr. Walker, of the Manly Seagulls Surf Club.

“With his Hawaiian surf board he drew much applause for his clever feats, coming in on the breaker standing balanced on his feet or his head.”

Although Polynesian Hawaiians invented stand-up surfing (which they called heʻe nalu = wave sliding) on carved wooden boards, it is highly likely the coastal Gayamaygal (from around present-day Manly) and Garigal Aboriginal clans of the Northern Beaches recreationally surfed Freshwater and neighbouring beaches, sat on open canoes.

Resembling modern surf-skis, their canoes were shaped from a single piece of bark prized from a Eucalyptus tree – typically box gum and red gum – which was fire-cured on one side causing it to curl, with the ends stitched together with hemp rope and insulated with mud.

According to Saltwater People of the Broken Bays by John Ogden, ”These were very good water people, with excellent surf skills. It was their livelihood. Theirs was a canoe culture and they were known to take these craft out in large surf.”