Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are advised that the following article contains discussion of Indigenous people who have died.

The Aboriginal Heritage Office have confirmed the human remains uncovered during excavation work to upgrade the sea wall at Little Manly Beach are of Indigenous origin.

On 26 July, Manly Observer reported that the remains discovered the previous day during construction work at Little Manly Beach were identified as human bones. However, after analysis by an archaeologist, it was determined that they are not of this era.

After the discovery, which followed on from sheep bones found in the ground the week before, Northern Beaches Council issued the following statement:

“Work has ceased at the construction site, and it is now under Heritage NSW jurisdiction with the Aboriginal Heritage Office and Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council operating under their authorisation.”

The Aboriginal Heritage Office (AHO) released the following confirmation: “Aboriginal ancestral remains were found at two locations during earthworks at Little Manly Reserve, Manly, on Monday, 25th July (Burial 1) and Wednesday, 3rd August 2022 (Burial 2). The NSW Police attended.

“On confirmation that the remains were traditional Aboriginal burials, they were recovered by the Aboriginal Heritage Office (a partnership of six councils – Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, North Sydney, Northern Beaches, Strathfield and Willoughby Councils) and Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council, as authorised by Heritage NSW.”

The AHO also reported the positioning of the remains: “The two burials were both flexed (knees up and hands near the face), on their left sides and the alignment was roughly east-west with the top of the heads towards the west. There were fish and shellfish with the bodies and some stone artefacts.”

A similar suspension of construction work took place in October 2021 during the upgrade of Clontarf children’s playground when bones were discovered in the ground. On that occasion, after NSW Police activated a crime scene, forensic analysis determined that the bones weren’t human.

Relocation or repatriation?

So what happens to the human remains now? The AHO issued the following statement:

“If the remains cannot be kept on-site safely and respectfully, they are removed with the aim of repatriating (reburying) them to a safe place. If MLALC and Heritage NSW support further analysis before repatriation, the remains are generally taken to the University of Sydney’s Shellshear Museum. Radiocarbon dating is carried out if possible.”

A spokesperson for Heritage NSW told Manly Observer, “The Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC), in consultation with the community, is considering radiocarbon dating of ancestral remains discovered at Little Manly Beach in July.

“Heritage NSW continues to work with the MLALC to repatriate ancestral remains on Country. Through repatriation, Heritage NSW supports the return of Aboriginal ancestors and objects to their rightful owners and resting places.”

Repatriation of Aboriginal remains is a sensitive cultural matter and both Heritage NSW and MLALC ensure appropriate awareness and protocols are followed when working with Indigenous communities.

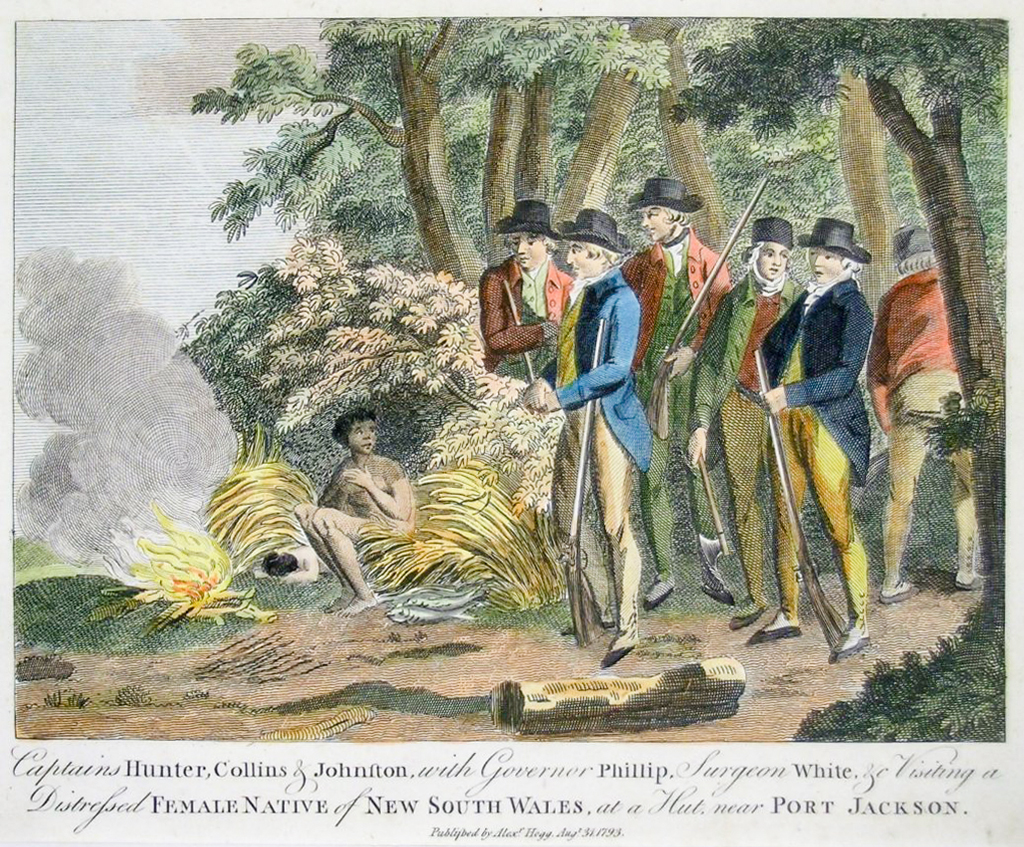

The Aboriginal Heritage Office noted, “It is important to remember that Aboriginal burials and ancestral remains have been disrespected by non-Indigenous peoples from the earliest days. For example, on a survey of Middle Harbour between 21 and 24 April 1788, Governor Phillip found the grave of a cremated Aboriginal person. He ordered that it be exhumed to determine the method for farewelling the dead.

“Traditional Aboriginal burials have many differences to other funeral practices since 1788 and they also vary from region to region across NSW and Australia…

“Most Aboriginal sites in today’s immediate coastal environment are likely to be associated with rising sea levels and fluctuations between 7000-3000 years ago. The oldest burial in the region is ‘Narrabeen Man’ dated to around 4000 years ago.”

Little Manly’s tragic history

The post-colonial history of Little Manly Cove, situated between Smedley’s Point and Little Manly Point, and the adjacent Spring Cove to the south, is replete with tragic circumstances that resulted in unfortunate deaths.

The Indigenous Birrabirragal people knew the inlets as Kayoomay, whilst the larger North Harbour, (including Manly Cove) was called Kayeemy.

Before the discovery that the bones at Little Manly were of Indigenous origin, there was a high possibility that the remains were of early European settlers.

What was also highly plausible is that they were Aboriginals killed by the 1789 Smallpox Outbreak.

Smallpox

When Europeans arrived in 1788 to establish their penal colony, there were around 29 Aboriginal clans resident across what came to be known as greater Sydney.

In April 1789, a smallpox contagion broke out among them, with devastating consequences. First Governor Arthur Phillip estimated that around half the Aboriginal populations living around Sydney Cove died, but historians have since revised the figure upwards to between 60 to 90 per cent.

Smallpox had a 30 per cent mortality rate, but it didn’t affect the British colonists because many of them had been exposed to the disease in their infancy and had basic immunity. However, without previous exposure to the smallpox virus, Aboriginal people had absolutely no resistance.

Those badly affected by the contagion included the Gayamaygal and Birrabirragal clans around North Head and Manly Cove.

Oral recollections from surviving Eora asserted that Aboriginals camped at Balmoral accepted blankets from the British “with red markings on them, a stripe of words or a crown” – the same as Royal Navy blankets of the era. They soon afterwards succumbed to a disease that inflicted ‘fire under the skin and the pus of a thousand festering sores’ – consistent with smallpox infection.

Royal Navy Marines accompanied the First Fleet to Sydney Cove (and were later responsible for the military coup known as the Rum Rebellion). However, with a severe shortage of ammunition, limited means to repair damaged and unreliable flintlock rifles, and a decline in numbers from their original contingent of 212, they were ill-equipped to deal with growing Indigenous resistance to the British military garrison expanding from Sydney Cove.

And a possible source of smallpox? First Fleet Surgeon John White brought ‘variolas matter’ – pus extracted from a smallpox sufferer and sealed in a glass bottle, which preserved it for years – with him from Britain, for the purpose of inoculating British settlers.

By the time Government Surveyor James Meehan surveyed the region in 1809 (who gave the name Little Manly to the small bay southeast of Manly Cove) it was sparsely-populated and most of North Head area was granted to an emancipated convict, butcher Richard Cheers.

Martha wreck

In August 1800, the Martha, a sealer and merchant vessel, whilst returning from Reid’s Mistake near Swansea Heads (named after its captain, William Reid, who discovered Lake Macquarie), took shelter from a fierce storm in Little Manly Cove.

Laden with coal, the anchor cable snapped and the 30 tonne schooner was driven onto a reef of rocks and holed, causing the death of four crew. The vessel was re-floated and sailed to Sydney Cove but found irreparable.

Lady MacNaghten and quarantine

On 26 February 1837, the ‘Fever Ship’ Lady MacNaghten arrived in Sydney from Cork, Ireland, with a surplus of potatoes (taking up vital space that triggered hygiene problems) and similarly overcrowded with 444 passengers and crew.

Typhus spread through the unsanitary conditions and 56 female emigrants, most of them children, perished on the sea voyage and were thrown overboard, while 17 others, including the ship’s surgeon, Dr Hawkins, died soon after their arrival.

Upon entering Sydney Harbour, 90 on board were reported ill with Typhus fever, 70 of them too weak to move. The 500 tonne barque was immediately diverted to Spring Cove on Governor Bourke’s orders and remained in quarantine until 10 May.

A makeshift quarantine station of canvas tents was established on the headland between Spring Cove and Little Manly (where Dr Hawkins was buried on 2 April). Here the passengers, whose clothing and bedding was burnt, were interned under the supervision of armed guards, whilst the more severe cases were treated on board the vessel, now a hospital ship.

After Lady MacNaghten, another 14 British emigrant ships were quarantined between 1837 and 1841, all for typhus fever – an average of one in ten of the vessels bringing new settlers to Australia.

Three months after their arrival, Lady MacNaghten’s surviving passengers were permitted to rejoin society. The Lady MacNaghten tragedy was instrumental in the establishment of the permanent Quarantine Station near Spring Cove above Cannae Point, North Head. The quarantine facility operated from 14 August 1832 to 29 February 1984, processing around 16,000 people, including those infected by the bubonic plague that arrived in Sydney in January 1900.

Many of those who succumbed to their illness are buried in the Quarantine Station grounds.

From smallpox to typhus to bubonic plague, North Head area, it seems, has a high body count.