Distinguished surfer and cyclist Matt Formston returned to the Northern Beaches – where he grew up – this week (2 November) to help instruct and inspire a group of youths with varying disabilities and special needs in surfing lessons at Manly Beach.

For those unfamiliar, Matt Formston is a multi-award-winning athlete in both tandem cycling (a former Paralympian, World Champion, World Record Holder and World Cup Gold Medallist) and surfing. He is the current Paralympic Surfing World Champion, winning the 2017, 2018 and 2020 International Surfing Association World Paralympic Surfing Championships.

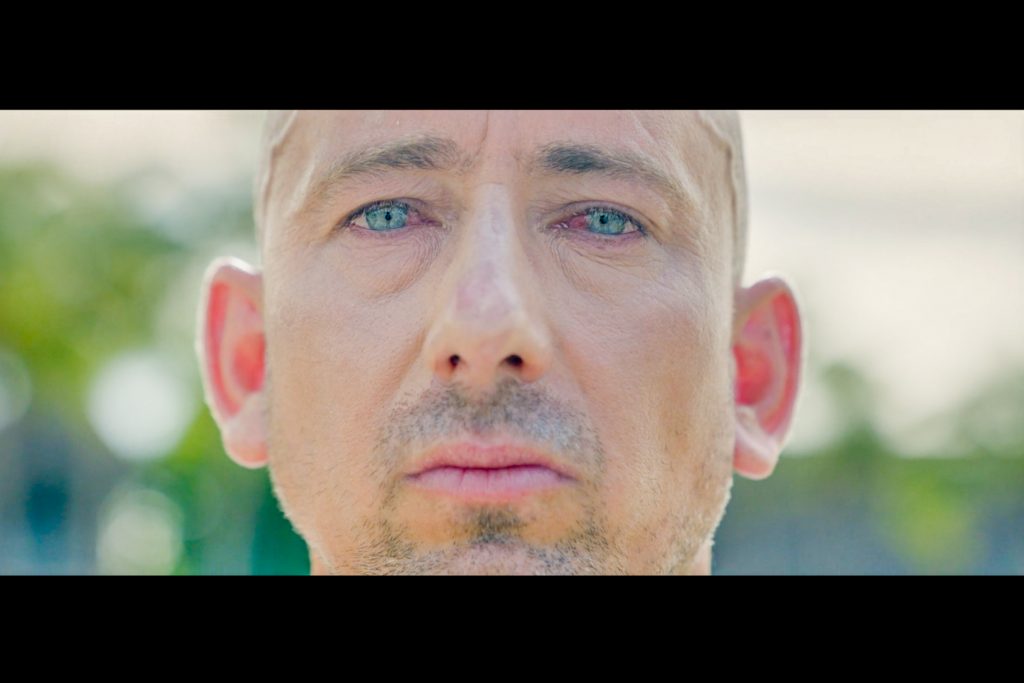

Matt is also what is termed ‘legally blind’, with limited vision around the periphery of his eyes, which makes his incredible athletic achievements significantly more wonderful.

Matt Formston’s cycling career began in 2009 while undertaking a Sydney to Melbourne charity ride for the Macular Disease Foundation, which he completed on a single bicycle. Thereafter, he rode competitively on tandem bicycles with sighted ‘pilot’ riders, including professional riders Phillip Thuaux, Mick Curran and Nick Yallouris, with whom he won many national and international sporting medals.

Building confidence

Matt’s autobiography on his webpage reveals how he gained confidence after his eyesight deteriorated with macular dystrophy at a young age.

“I was born with full vision but lost 95% of my vision when I was five. The doctors and my teachers said I had to leave my mainstream school and go to a school for people with disabilities, they said I would never play sport and they said any career aspirations were basically over.”

However, Matt, who attended St Augustine’s College in Brookvale, followed by Forest High School in French’s Forest, persisted and excelled.

“My parents kept me in the main stream school, they enrolled me in sport, and instead of saying ‘Matt can’t do that,’ said: ‘let’s try it and if Matt can’t do it then let’s find a plan B.’

“We never really had to look at plan B, because with a desire to achieve, a desire to prove I was not disabled and a lot of Aussie mongrel we found a way.

“I’ve now been a professional athlete for over a decade, I’ve been fortunate enough to be sponsored by some of the biggest global logos in sport. Despite being blind, I’ve always had a clear focus on my goals and my why.

“As a cyclist, my ‘why’ was to prove to myself and the world that with the right mindset, behaviours and work ethic you can become a world beater. My ‘why’ in surfing is because I absolutely love everything about surfing and to be able to compete in the sport that I love is an absolute bonus.”

The Blind Sea

Matt, who began surfing aged 11 and rode his first wave on a board at Warriewood Beach, was also in Manly to continue film-work on The Blind Sea, the imaginatively-named feature-length documentary on his life story, directed by Daniel Fenech of Brick Studios.

Due for completion and release in 2023, The Blind Sea is following Matt’s current progress from the uncommonly calm Manly Beach – with little ripples well-suited to the beginners in Matt’s class attempting to straddle foam boards – to a big wave surfing record attempt this month.

Matt’s next challenge is to surf the Atlantic waters off Nazaré, Portugal, where a combination of geographic and tidal characteristics produce ‘monster’ sized waves at certain times of year, typically October to November.

And ‘monster’ is the operant word – if one of these big fellas rolled into Manly the Corso would redistribute itself between the CBD and Parramatta in a matter of minutes.

Riding monsters

According to the NASA Earth Observatory, “In winter, the waves off North Beach (Praia do Norte) average about 15 meters high. On an exceptional day, surfers can catch a wave towering around 24 meters…

“The waves here are magnified and focused by a deep underwater canyon measuring 210 kilometres long and coming to an end at Nazaré Bay.”

On 29 October 2020, the record for the highest wave ever surfed – 26.21 metres by Sebastian Steudner – was set, beating the previous record of 24.38 metres by Rodrigo Koxa on 8 November 2017.

However, on the same day, António Laureano, rode a wave estimated to be 30.9 meters in height.

Although this achievement is still awaiting confirmation by the World Surf League (who work with the Guinness World Records to ensure accurate, standardised measurements), all three of these record-breaking rides took place at Praia do Norte in Nazaré, Portugal – where brave Matt is headed.

After winning the Association of Adaptive Surfing professionals world tour in September 2022, Matt was approached by Australian surfing legend Dylan Longbottom – big wave rider and boardmaker – who suggested Matt attempt to break the record for the biggest wave ridden by a blind surfer. Longbottom’s crew will take Matt to Nazaré for the attempt.

The unofficial record, at 4.5 metres, by a non-sighted surfer is currently held by Brazillian Derek Rabelo at Nazaré. Rabelo, who was born blind from congenital glaucoma, received surfing instructions from two-time world champion Tom Carroll, who hails from Newport on Sydney’s Northern Beaches.

Overcoming anxiety

Matt admitted to Manly Observer that he was a little anxious about the Nazaré trip.

“I’m feeling as confident as I can. It’s known for the biggest surfable waves in the world and also the most dangerous waves in the world… But I’ve been training really hard for it. My team feel I’m capable of it.. so it’s now time to commit to it.

“I’m excited, nervous, honoured – all those different emotions!”

To be considered a big wave surfer, the rider must tackle an upsurge over 6.2 metres in height. Surfers typically ride boards known as ‘guns’. These are between two to four metres in length, narrower and significantly thicker than a regular board (the former for speed, the latter for durability), with up to four fins, plus the recommended element for digging into and manoeuvring on the massive wall of water behind: a round tail.

Belharra (near the Basque Pyrenees), California, Canary Islands, Hawaii, Oaxaca (Mexico) and Tahiti produce massive swells, but Nazaré in Portugal has become synonymous with the breaking of big wave riding records.

Iconic images show the 16th Century fort and red lighthouse on the shoreline of this small seaside town are routinely dwarfed by the freakishly high crests that roll in from the North Atlantic Ocean, often peaking at 30+ metres.

To appreciate how daunting it is plunging down the face of a sheer wall of water this size, which can travel at up to 80km/hr, you need to have incredible physical strength and agility. And, of course, the ability to hold your breath for up to four minutes if you fall off and plummet into the estimated 400 tonnes of water.

To take into consideration the aforementioned factors for a rider with almost zero sight, in a 2021 ABC TV interview, Matt described his limited vision.

“I’ve got big black dots in the centre of my vision. My vision disorder is called macular dystrophy. I think a lot of people would know what tunnel vision is. Mine’s basically the opposite of that. So, I’ve got nothing in the centre at all and then the outside is really, really blurry.”

Training to ride monsters

Matt revealed to Manly Observer how he is training for the Navaré challenge.

“There’s physical training in the gym and breath training in the pool.

“I’m training physically in the gym to get my body strong enough to handle those huge waves. And I’m doing breath training, so I can hold my breath for a long time but also tolerate high levels of carbon dioxide from holding my breath. Most people think holding your breath consists of keeping still and not breathing in for a long time – which I can do for five minutes if I’m sitting still with my heart rate low.

“However, when you’re doing big wave surfing your heart rate is quite elevated – obviously that’s the nature of an extreme sport – so the problem is the high levels of carbon dioxide rather than low levels of oxygen. So it involves training your body to function with high levels of carbon dioxide, getting used to the processes.”

How will he manage dropping into those monster waves on his board when they come rolling in, if he can’t see them?

“We’re using different cues. Normal guys that can see, when they’re behind the jet-ski and being towed on a rope, they’ll see when they need to pull themselves into a wave and let go of a rope. But I can’t see that.

“So with the guys on the jet-ski we’ve worked out different processes. They’ve got a referee whistle, so they’ll blow it when I need to let go of the rope as I pull into the wave. They’ll make sure the time is right when they’re confident that I’m heading into the right waves and in the right spot.”

What if things go wrong and he takes a tumble?

“If I’m in a bad situation, I’ll have that jet-ski and at least two other safety skis that can come and get me if I wipe out. If we get into a situation where there’s a wave that’s about to break on me but they can’t get to me on time, they’ll have an airhorn they can blow.

“People haven’t done this before, it’s new, so we’re working out the processes whereby we can take on something that’s never been done, but do so in a safe way by removing as much risk as possible.”

Matt Formston Webpage

The Blind Sea film

Matt Formston Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/mattformstonofficial/

Matt Formston Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/mattformston/

Macular Disease Foundation

https://www.mdfoundation.com.au/